The great white is one of many shark breeds in the Santa Barbara Channel, and the community was once again reminded of its presence when a UCSB student was attacked and killed in Lompoc on Oct. 22.

Local ocean users, however, haven’t let the attack keep them out of the water.

Scott Fickerson, surf instructor at City College, grew up surfing in Ventura. He has a 17-year career behind him patrolling the same beaches as a lifeguard.

During his years of ocean activities in California he has encountered a few sharks, but that’s not something he finds demoralizing.

“We’re in the ocean, which is the shark’s environment,” he said, acknowledging that there will always be a risk when you’re out there. “But [the risk] is so remote that it’s really not worth worrying about.”

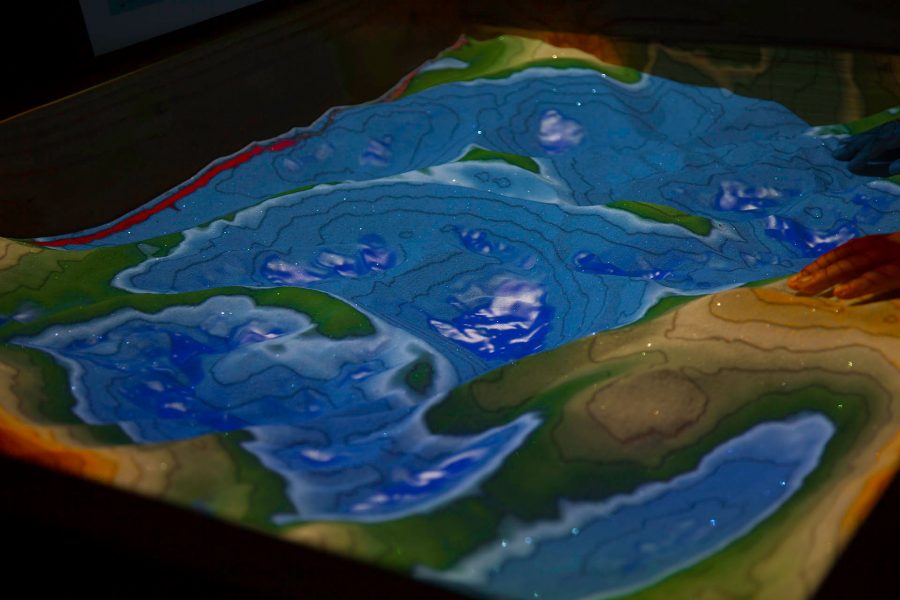

One of the main reasons Fickerson isn’t concerned when surfing in Santa Barbara is its protected location. Even though the shark crammed channel runs through these waters, the animals’ actual trail is miles out into open ocean, connecting Point Conception in the north with Point Magu in the southern part of the county.

Surf Beach, where the fatal attack occurred, is right by Point Conception, and several shark attacks have been reported there in the past.

The City College surf class goes out Tuesday and Thursday mornings to Leadbetter Beach below West Campus, but Fickerson said no one has asked to be excused because of the recent attack.

He always addresses the risk at the beginning of each semester, but unless there is a specific shark warning, the class will run according to schedule, he said.

Jim Holmer, 38, is a local surfer who follows the swells around the county. Even though he said he surfed close to Surf Beach the same day of the attack, Holmer doesn’t like to think too much about the potential danger.

“On a daily basis when I’m out there, I won’t think about sharks,” he said. “It’s much more dangerous to drive on the freeway.”

Even though most nearby beaches have been spared, recent years have seen a peak in shark attacks in California with 37 documented cases since 2000.

Of the reported sightings on the Shark Research Committee website, many are from popular Los Angeles locations such as San Onofre State Beach and Sunset Beach, and La Jolla in San Diego County.

Although, Marine Biology Instructor Michelle Paddack points out, because of the popularity of these spots, there will be more people to report sightings – it doesn’t necessarily mean there are more sharks out there.

However, “surf season” in Santa Barbara, which is just getting started with northwest ground swells rolling in, is on the other end of the calendar from what some believe to be “pupping season” for the great whites.

Dr. Michael Domeier, marine biologist and president of the Marine Conservation Science Institute, presented a theory that the great white comes into more shallow waters roughly between April and August to give birth, and even though the offspring are not a threat, the mothers can be.

Juvenile sharks are, however, a threat to sea lions and seals, as shown this summer when numerous wounded and dead animals were found along the Santa Barbara coastline.

However, Fickerson said dead seals and sea lions are often mistaken for shark victims, when they may in fact have died for other reasons.

“You can see indications in the springtime [of many juvenile white sharks], such as poorly bitten seals,” Paddack said.

She also clarifies that predators such as the great white give live birth, so any shark eggs found on the beach are most likely from “little guys” such as Horn, Leopard, or Swell Sharks.

Like Fickerson and Holmer, Paddack says you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than attacked by a shark, and she sees no reason to stop enjoying the ocean.

“We know less about the ocean than we do about the moon,” she said. “There is no evidence that any particular behavior [of human beings] make us more prone to shark attacks.”

![Milton Alejandro Lopez Plascencia holds a flag showcasing the United States and Mexico on Feb. 7 in Santa Barbara, Calif. “It’s heartbreaking to see what is happening all across the country,” Lopez Plascencia said. “I [want] my voice to be heard by the community.”](https://www.thechannels.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MGSImmigration-1-1200x800.jpg)

![The new Dean of Social Science, Fine Arts, Humanities and English, Eric Hoffman beams on May 2 in Santa Barbara, Calif. "My major professor in college [inspired] me," Hoffman said. "You can really have a positive impact on people's lives in education."](https://www.thechannels.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MGSHoffman-2-1200x800.jpg)